Gripping Post office drama has exposed deep flaws in our British justice system

Just a few hundred yards from our offices in Llandudno is a quiet side street that has become the unlikely epicentre of the biggest miscarriage of justice in British history. Today number 21 Queens Road is a fundraising outlet for St David’s Hospice but in 1998 a Mr Alan Bates and his partner Suzanne Sercombe moved from Halifax to Llandudno, and took over the premises. They developed a thriving wool and clothes shop called the Wool Post, and also ran the small Craig-y-don branch Post Office next to the store.

The following year the Post Office installed a new Fujitsu Horizon computer system into the branch, and just two months after the installation was completed Mr Bates received a call with the shock news that there was a ‘variance’ of £6,000, and that contractually he was liable to make up the shortfall. He wasn’t allowed to see the Horizon calculations but was assured by the Post Office that his was a unique event.

By 2003 Alan’s contract had been terminated, wiping out the life savings he had invested in the business. This might have destroyed any average person but – as viewers of the gripping Mr Bates vs The Post Office ITV drama have discovered – Mr Bates was no average person, and he certainly wasn’t alone.

The scandal saw 736 Post Office staff prosecuted and some even sent to prison based on data which was later found to have been altered by “bugs, errors and defects”. Many of the victims were forced to declare bankruptcy and resorted to selling off their homes to make up alleged losses; most suffered severe mental and personal trauma, marriages and families disintegrated and four victims – Martin Griffiths, Fiona McGowan, Peter Huxham and and Louise Mann – even took their own lives.

In every case the Post Office relied on the argument that the shortfall was a completely isolated occurrence, but by 2020 some 2,500 people had lodged claims alleging system errors.

In the drama Mr Bates, who still lives locally, is quite accurately portrayed as exactly the kind of person who strikes terror and panic into any corrupted organisation. He wasn’t a vociferous campaigner or a tub-thumping activist, rather Mr Bates was possessed of a quiet, determined and utterly relentless conviction that an injustice had been perpetrated and it needed to be acknowledged and rectified.

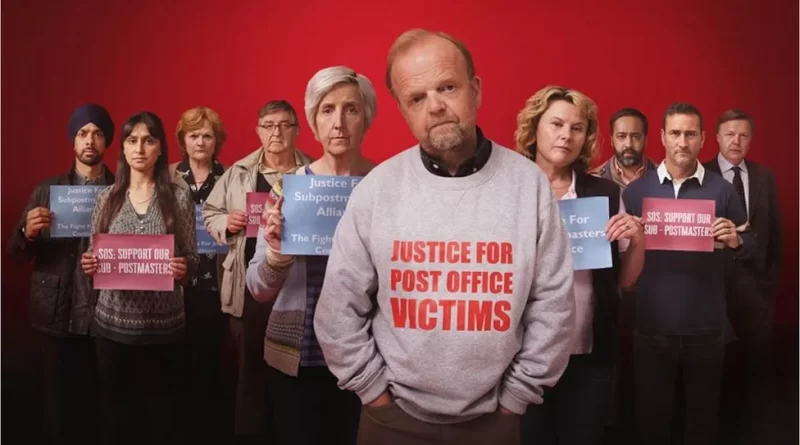

The ITV drama, in which Mr Bates is played brilliantly by actor Toby Jones has shocked all who’ve watched it. But as Jones himself has noted, Mr Bates was not the easiest character to play.

“I went to chat to other people who knew him, and they said Alan Bates is one of the smartest and most inspirational people they’d ever met,” said Jones.

“All of my dealings with him have been great…. [But] they haven’t helped me play him very much. He wasn’t a great source of material – he was very friendly and warm, but he said, ‘The thing is, I’m not a very emotional guy.’ There is a paradox about him.”

Such observations will come as no surprise to anyone who has been involved in social justice campaigning issues. Taking on large corporations, civil organisations or even governments is not a quick and easy process, especially when some great wrong has been perpetrated and those in positions of power become pathologically ruthless in protecting their reputations and high salaries. A slow and incredibly dogged persistence in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds and setbacks is invariably the only path to justice when corporate entities are involved.

What made the Mr Bates vs the Post Office drama so impactful was that it ran like an exceptionally well-crafted crime drama, except for the fact that you couldn’t escape the unease that this was no play-script, but an anguished narrative of the utter destruction of very real people’s lives.

All of those involved in the production of the drama – actors and real subjects – have said that they wanted to produce the series to ‘speed up’ the exoneration and compensation processes, which appallingly are still being dragged out doggedly some 25 years after the events first came to light. Whilst the air is full of half-apologies and promises, there has been little meaningful done in terms of properly compensating the victims.

One of the most common responses to the TV series has been exasperation, with many on social media claiming the injustices exposed in the drama made them feel “sick to the stomach”. The biggest – and most angry – questions related to the time this case is taking to resolve, and the inability of numerous individuals and organisations to simply accept quickly that errors had been made, and to find equally speedy mechanisms to resolve them.

Sadly, the experiences of the post workers in the Mr Bates vs the post Office saga only underscores longstanding and fundamental deficiencies in both the British justice system, and the ways in which individual human worth is calculated in contemporary British society.

In 2019, after years of battling Fujitsu, the GPO and the government the Post Office agreed to pay £58 million in compensation to those from the campaign group who had been falsely prosecuted, after what Judge Fraser described as the Post Office’s “institutional obstinacy” in accepting that there were issues with the Horizon computer system. But after legal costs the group were left with just £12m, or £20,000 each. So the barristers, legal teams and others involved in righting this profound injustice netted a whopping £46m for their efforts – almost three quarters of the compensation payout!

Elsewhere Fujitsu remain relatively untainted and unaffected, despite having introduced a critically important computer system that they knew early on was riddled with faults that could lead to the potential prosecution of innocent people.

At the head of the Post Office and overseeing the prosecutions was CEO Paula Vennells, a British businesswoman and (somewhat ironically for the moral dimension of the case) a former Anglican priest who had previously worked for L’Oreal, Argos, Dixons Retail and Whitbread, and who also held non-executive directorships at UK supermarket chain Morrisons and furnishings group Dunelm.

In the 2019 Queen’s New Year Honours, Vennells was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) “for services to the Post Office and to charity” – despite the fact that the scandal had already reached very significant levels by this time. Vennells has offered a brief apology for the distress the saga caused but despite calls for her to be stripped of her CBE, the government has failed to respond. Unfortunately for the government, in the wake of the TV drama, an online petition to strip Vennells of her CBE has exploded through the required 100,000 mark for the issue to require discussion in parliament. No doubt if televised this particular debate is likely to attract as many viewers as the TV drama!

Whilst the protection of institutions, personal reputations and significant incomes will come as no surprise in a British culture current sunk beneath a sea of nepotism, self interest and meritocracy, the Mr Bates saga has also exposed a far more fundamental obstruction to moral justice in our cherished British legal and cultural system.

As I watched the Mr Bates vs the Post Office episodes I couldn’t help but see echoes of the late Cardinal Basil Hume’s lengthy and often frustrating fight to overturn the convictions of the Guilford Four and the Birmingham Six. After Basil had been alerted by Belfast MP Gerry Fitt to the plight of Guiseppe Conlon, who had been jailed on questionable explosives charges, the cardinal engaged in a determined campaign to secure his release, but became increasingly frustrated and distressed by the lack of interest and co-operation from everyone – from police offers to senior judges, from civil servants and even successive home secretaries.

Even his last desperate appeal to the then Home Secretary William Whitelaw to release the dying Conlon on health grounds was ignored, and the cardinal remained forever haunted by the fact that he couldn’t help a man who had died a terribly lonely death whilst consistently, and correctly, protesting his innocence.

Here lies perhaps one of the greatest inadequacies of the British legal system, and one which has impacted equally on the victims of the Post Office scandal. Few people really understand how sacrosanct a conviction in law really is, and therefore cannot understand how overturning an injustice is no simple matter of acknowledging an error and correcting it. Once a judgement is delivered it acquires the status of a sacred text, part of the great historic body of case law and precedent that is the fundamental building material of our unique British legal system.

Thus to question a legal judgement is to question profoundly the system that gave rise to it, and this simply cannot be tolerated. Hence the familiar conundrum where a convicted prisoner cannot get early release if they continue to protest their innocence, and which is why we hear of cases of innocent people being persuaded to plead guilty in order to receive shorter custodial sentences. Indeed, some of the victims in the Post Office scandal went down this very route, only to now find that the British legal system is understandably reluctant to quash the convictions of any individual who has voluntarily pleaded guilty to a crime.

My greatest concern about the Post Office case, and I’m betting it’s the one that has worried other people most, is that here we have some 2,000 innocent, hard-working individuals who were going about their lives being not only good, law-abiding and decent citizens but were actually providing a fundamentally important social good within their local communities.

Through no fault of their own – and without warning – they suddenly found themselves profoundly at odds with the dark, unseen institutional and ambitioned mechanisms that really hold the fiscal and political systems of Britain together, and their lives were destroyed systematically and without compunction.

Any one of them could be any one of us, and that’s extremely disturbing.

We Catholics tend to talk a lot about the interface between faith and politics, but a lot more work needs to be done, and as quickly as possible, to ensure that there is a proper moral dimension embedded into public life so that protracted injustices like the Post Office scandal can never be repeated. Please do keep all the Post Office campaigners in your prayers as they continue their long fight for justice and exoneration.

Joseph Kelly is Catholic writer and theologian