Say a prayer that peace and common sense prevail this Remembrance weekend, says Joseph Kelly

After what has been yet another week of political controversy and uproar, the country is understandably holding its breath ahead of tomorrow’s start of a weekend of Remembrance events.

Reactions to Israel’s invasion of Gaza have been spilling over onto UK streets in recent days, so there was some considerable need for politicians to calm the air. Instead, what we got was an unprecedented escalation of tensions after Home Secretary Suella Braverman wrote an article in The Times on Wednesday accusing the Metropolitan Police of bias over its handling of public demonstrations.

In the article – which hadn’t been authorised by Downing Street – Mrs Braverman claimed that in recent protest incidents aggressive right-wing protesters were “rightly met with a stern response”, whilst “pro-Palestinian mobs” were “largely ignored”.

She went on to say police were applying “double standards” and “played favourites when it comes to demonstrators”.

The article caused shock and outrage in many quarters, not least from members of her own party who were quick to distance themselves from the remarks. It later emerged that Downing Street had been shown a pre-publication draft of the article and had called for Mrs Braverman to tone down the text, which she refused to do. There’s now a formal investigation under way as to how the article came to be published without the changes requested having been made.

In what is a remarkably fragile and potentially incendiary time for politicians of all parties, there was clearly an opportunity for both the Opposition and members of Mrs Braverman’s own party to point-score but no-one seemed quite certain on the best stance to take. After all, these days it’s all but impossible to anticipate the public zeitgeist, and even the most carefully targeted of political barbs can easily misfire, and badly.

Whatever the personal view on Mrs Braverman’s comments, the fallout has homed in on whether or not the article has compromised the political position of the Home Secretary to the extent that the PM needs to remove her. So far Mr Sunak “still has confidence” in his colleague, but that’s a phrase often found at the edge of a cliff.

For the Metropolitan Police such criticism is an irrelevant happenstance for an organisation that has not only been struggling for decades to define its place in our modern ‘democratic’ society, but to control the increasingly volatile and irrational body of the general public.

In times past it was considerably easier to both control and protect the public in situations of conflict and protest – the arguments and divisions of any situation were clear to see, and thus dealing with unrest and maintaining public order was relatively straightforward.

One of the problems heralded in by the digital age is that civilised public protest – which is a healthy marker of any democracy – very quickly morphs and dissipates into a whole range of issues and grievances that become attached to the original purpose. This makes the control and policing of any public event incredibly complex and difficult as, by the time people hit the streets, countless agendas and subplots are in play.

One only has to look at this coming Remembrance weekend events and the planned pro-Palestinian marches to see that it was only ever going to take the slightest of excuses to bring all kinds of unwelcome factions into the mix, with all the uncertain and potentially catastrophic consequences that could bring.

From what we could tell, there was initially no intention to bring the Gaza marches into conflict with long-established Remembrance events, indeed there were the strongest possible affirmations from the organisers that one would respect the other. After all, these were hardly conflicting ideologies – one event commemorating the dead of numerous bloody conflicts, and the other trying to stop yet another dreadful war being added to the list!

Given that public order has been hanging on a knife edge all week, one has to wonder what on earth was going on in the mind of our Home Secretary.

Neil Basu, the former head of the UK’s counter-terrorism police, was in no doubt. Speaking on the BBC’s Today podcast, Mr Basu said that Mrs Braverman’s comments were “tantamount to effectively trying to direct the police” and warned that the UK was “in danger of turning the police into an arm of the state directed by politicians”.

Unfortunately, Mr Basu, that happened quite a long time ago, when Mrs Thatcher redefined the historic police/state relationship, which had been primarily the protection of the public rather than the state. In the 1980s, crashing through the miner’s strikes, the Wapping dispute and the poll tax riots the Thatcher administration pulled the police under its protective wing, earning it the sobriquet “Mrs Thatcher’s boot boys”.

Almost half a century on the force is still struggling to shed this legacy and frankly Mrs Braverman’s ill-timed article may well end up putting these efforts right back into the 80s.

Whether or not the Met could have controlled this weekend’s events adequately we’ll never know, because the fallout from the Times article has this evening forced them to impose an exclusion zone around the Cenotaph, which isn’t even close to the planned route of the pro-Palestinian march.

Since the Gaza conflict began, the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign has organised three national protests in London on successive Saturdays. Whilst each one has grown in size they have been largely peaceful and the organisers have worked closely with the police to ensure this has been so. To their credit, the police have in turn done an excellent job of managing the difficult balance between free speech and law and order.

But as the Met know from hard past experience, confrontational decisions such creating an exclusion zone is just an invitation in this day and age for outfield agitators, splinter groups and plain hooligans to head out and try their luck.

Earlier this week the Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley was being adamant that the legal threshold allowing him to ask the Home Office for permission to ban the march had not been met, and he also stressed that there are actually no powers in current UK law to ban a static demonstration.

Clearly a week is not only a long time in politics, but in policing also.

What makes these events particularly ironic is that the very people being commemorated this Sunday are those most likely to have had deep empathy for what the pro-Palestinian marchers are trying to achieve. After all, the essence of the protest marches this weekend is going to be a call for a ceasefire, to allow innocent civilians to leave Gaza, and for humanitarian aid to get in.

Those who paid the ultimate price at Ypres, Normandy or Afghanistan would surely have understood that basic human plea. After all, they fought and died principally to bequeath us the right to walk freely, and protest freely, on the streets of Britain.

It’s not unreasonable, therefore, to argue that the government’s actions this week are an affront to the very Remembrance events they are claiming to protect.

At the darkest level, fuelling public anxieties about the possibility of rioting on the streets is an old weapon often favoured by dictatorships, and used as a tool to strengthen and tighten public order and assembly laws. But governments enact such legislation at their peril, as thankfully history has taught us that law is never ‘stronger than life, and man’s desire to be free’.

After all the upheaval and political animosity of the past 48 hours, let us say a prayer that this weekend peace and common sense will prevail at all the events being organised, so that those we are commemorating may keep their rest, and know that the democratic principles they fought and died for have held.

…………………….

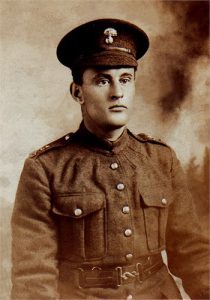

This article is dedicated to my great uncle, Edward Kelly of Trenadullgh, 19939 7th/ 8th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers who died aged 24, on 22nd August 1917 in Vlamertinghe, Belgium. Remembered with honour, Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium.

This article is dedicated to my great uncle, Edward Kelly of Trenadullgh, 19939 7th/ 8th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers who died aged 24, on 22nd August 1917 in Vlamertinghe, Belgium. Remembered with honour, Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium.

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain.

Nor shall he know when loud March blows

Through slanting snows her fanfare shrill,

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

But when the Dark Cow leaves the moor

And pastures poor with greedy weeds,

Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn

Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.

By Catholic war poet Francis Ledwidge, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Killed by a shell near Ypres, 31st July 1917.