Silence throughout the synod is probably wise, but decisions will need to be explained adequately

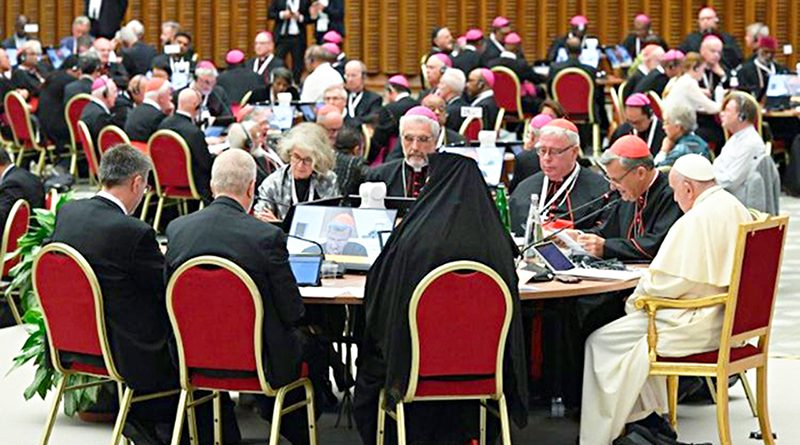

For months now it’s been hailed as the most important meeting of minds in the recent history of the Catholic Church, and an event could well produce seismic changes in Catholic doctrine. On the other hand critics have complained that it’s a gathering of extreme exclusivity, internecine agendas and intellectual pomposity when it’s premise is to remove exactly those negative traits from the Catholic establishment.

The Synod on Synodality has been such a long time in the making, and comes at a time when the Catholic Church has an urgent need to clarify and develop its theology not only for the benefit of the laity, but to reflect unprecedented social changes and global upheavals. For those of us old enough to remember it, this synod has much in common with the Second Vatican Council, which was convened under not entirely dissimilar circumstances.

“I want to open the windows of the Church so that we can see out and the people can see in,” said Pope John XXIII at the time.

The trouble that gave rise to Vatican II, and the trouble that Vatican II caused, was primarily due to the sexual revolution of the late 50s and early 1960s. After generations of social invisibility the younger population in particular had grown tired of the moral strictures of their parents’ generations, and so much that society had assumed to be inviolable was suddenly being challenged, or rejected completely. In the face of this moral stampede the Catholic Church had become like a besieged fortress defending itself against the imagined barbarians howling at its gates.

One might easily be forgiven for thinking we’ve arrived at a somewhat similar juncture today – what with the furore over gender politics, free speech, abortion, euthanasia, global conflict, the climate emergency and the polarisation of the immigration debate. And that’s before we factor in our deepening internal and theological divisions.

Little surprise then that many have marked up the Synod on Synodality as Vatican Three Lite.

It’s a nice thought – but just as Vatican II promised far more than it delivered, this synod may well go the same way, despite Pope Francis’ determination that he wants radical new ground to be broken.

As far back as 2016 Francis was revealing to his closest circle that it’s “not excluded that I will go down in history as the one who has split the Catholic Church” (at least according to the German magazine Der Spiegal – which didn’t give a citation!).

For some, this unique and often unpredictable pontificate has the seeds of fantastic expectation and radical reordering within it, for others that same narrative is deeply troubling, heretical even. Where you stand depends largely on whether you think the Catholic Church should lead the world, or provide an antidote to it.

Change in any organisation is never easy, and it’s especially difficult in an organisation where its central doctrinal premise is the eternal immutability of certain supposedly self-evident truths.

Pope Francis is in no doubt where he stands; he has a vigorous antagonism towards the structure and outlook of the contemporary Church, which he feels is suffering from a particularly negative and paralysing fortress mentality. More than a decade ago – in an interview after World Youth Day in Argentina – Francis made his position clear: “I want to see the church get closer to the people. I want to get rid of clericalism, the mundane, this closing ourselves off within ourselves, in our parishes, schools or structures. Because these need to get out!”

By November of that same year Francis had expanded these thoughts in his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium – On the Proclamation of the Gospel in Today’s World.

“I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security,” he wrote. “I do not want a church concerned with being at the center and then ends up by being caught up in a web of obsessions and procedures.” (EG,49)

We can only hope that a decade later the Synod will deliver the Catholic laity something that is both meaningful, and relevant to the kind of lives that ordinary Catholics in the street are having to live through at present. Few are present at this great gathering, and the Catholic concerns of the masses have been conveyed to the debating tables by a lengthy process of consultation and upward distillation that in any organisation is rarely a healthy formula for democratic consent or unanimity.

Such a mechanism also tends to create an equally unhealthy return of pronouncements, and even in the first few hours of this synod we’ve had several prime examples of this.

To take just one instance: earlier this summer a group of five cardinals wrote a letter to Pope Francis asking him to answer five ‘dubia’, or doubts, that they had relating to the synod.

Cardinals Walter Brandmüller (Germany), Robert Sarah (Guinea), Joseph Zen (Hong Kong), Juan Sandoval Íñiguez (Mexico) and Raymond Burke (USA) delivered their letter of concern to Francis on 10th July – but its contents, and the pope’s reply, was only made public this week.

Clearly the five cardinals felt that Francis hadn’t answered their questions sufficiently, or rather had sidestepped them theologically. Such was their consternation at the pope’s replies that they redrafted the five questions in a manner that all but required a yes or no answer. So far there’s no indication that Pope Francis has replied and frankly it’s unlikely that he ever will, as Francis is not a man to reduce the complexities of the Christian life to a simple – or rather entrapping – ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

The dubia that inevitably grabbed the media attention was the cardinals’ question about the validity of marriage and “other types of unions of a sexual nature”, and that the blessing of same-sex couples could give rise to a fundamental confusion amongst the laity about their validity, given that the Church otherwise regards such unions as irrevocably sinful.

Francis’ answer was well-crafted; and clearly too well-crafted for the five cardinals. His response also led many media outlets around the world to announce that Pope Francis was open to blessing gay couples. “Pope Francis suggests gay couples could be blessed in Vatican reversal,” shouted The Guardian on Tuesday in a conclusion that rang out similarly from media channels across the globe.

Like so many such Catholic pronouncements across my 40+ years in Catholic journalism, everyone is of course right, and everyone is in the same instant equally wrong. Things said between theologians can have many contrary meanings – it’s in the very nature of the narrative, just as it’s in the nature of journalists to make a headline, and the nature of protagonists to mould words to support their case. Sadly, it’s invariably left to the rest of us to make sense of all the clamour, and in particular for grass roots clergy and the laity to peer through the glass darkly and try to discern how such arcane arguments might possibly relate to their lived experiences.

Thus it comes as no surprise that yesterday, as the Synod was finally getting under way, Pope Francis asked its participants to avoid speaking to the press – and not just during the Synod but afterwards as well.

Dr. Paolo Ruffini, the Prefect of the Vatican’s Dicastery of Communications, confirmed that the information flow from the meetings will be “very limited,” suggesting yesterday that journalists can report instead on “the absence of news.”

It was an announcement that if nothing else revealed that the Vatican knows precious little about the motivations of the media – as trying to shut down controversy is the one sure fire way of putting every journalist on the case.

Perhaps some has pointed that out to the Prefect, who backtracked somewhat at today’s session, stating rather that “Every member of the synod makes their own discernment” in terms of whether to speak with the media.

“We are not speaking of punishment or not, but a personal discernment the Pope asked of the members, and the discernment is left to each individual person,” Ruffini said.

Sadly, the assumption that nothing ever needs to be explained properly, and then trying to hammer down on the discussion after the horse has bolted, is an all too familiar scenario when it comes to the expounding of Catholic teaching. To make matters worse, journalists have not been allowed access to this synod and, whilst there have been no non-disclosure agreements, “canonical penalties” apparently await those who do not maintain their silence, even after the synod is finished.

(Much the same applied to the Second Vatican Council, though inevitably some individuals did eventually let slip the odd story here or there!)

Not surprisingly, I’m pretty much on the side of the journalists, who are only ever trying to do their job in difficult circumstances. When I look back over some of the most inflammatory or damaging reports that the media has run about Catholic affairs across the past four decades, much of the damage could have been avoided if the Church had engaged and explained when matters first materialised. Few things are so terrible that they can’t be confronted, and they’re best confronted as early as possible; prevarication and procrastination invariably lead to rumour and exaggeration.

For the record on the Pope Francis gay blessings story, His Holiness reiterated that matrimony is a union between a man and a woman, but that “pastoral charity” might give a priest the justification to bestow a blessing on a same-sex couple, so long as this was seen as the Church expressing its love and concern for the couple, but absolutely not endorsing their sinful behaviour.

“For this reason, pastoral prudence must adequately discern whether there are forms of benediction, requested by one or more persons, that do not transmit a mistaken conception of marriage,” Francis wrote.

“Because when a benediction is requested, it is expressing a request for help from God, a plea to be able to live better, a trust in a father who can help us to live better.”

He said there were situations objectively “not morally acceptable” but the same “pastoral charity” required that people be treated as sinners who might not be fully at fault for their situations.

But Francis also added that these circumstances were exceptions rather than the norm, “because the life of the church runs on channels beyond norms”.

All of which makes perfect sense theologically, but also makes an entirely other kind of perfect sense to a non-Catholic journalist and headline writer.

Like I said, it’s one of the great joys and frustrations of being a member of the Catholic faith that on matters of import we are often all right, and we are often all wrong.

Given the events of the past few days, a silence throughout the synod is probably a wise decision, but sooner or later someone is going to have to tell the Catholic world exactly what we’re required to be thinking in the years ahead, and in a way that please God we’ll be able to understand and live with.

Joseph Kelly is a Catholic publisher and theologian.