There is a clear moral case for slavery reparations, but there’s unlikely to be any agreement on the process, says Joseph Kelly

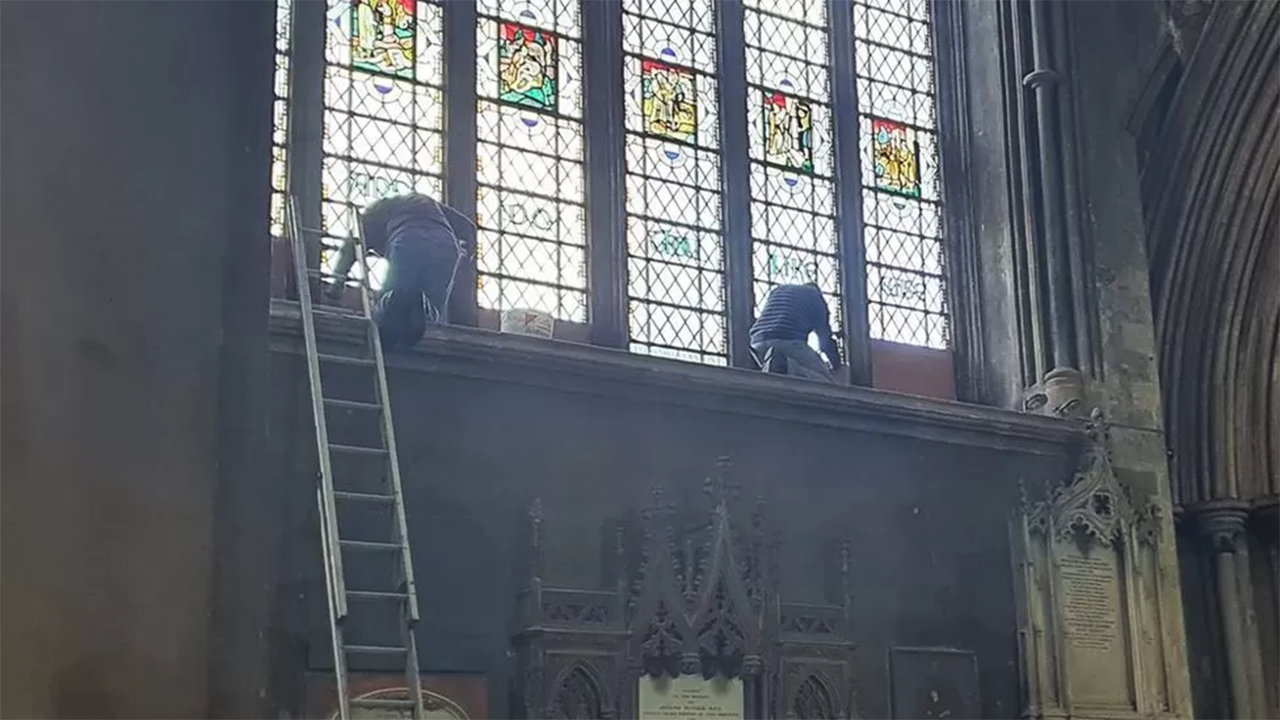

The lone workman who climbed his ladder this week to put the finishing touches to the new stained-glass panels in the church of St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol attracted little attention, but it may have been a defining moment in both ecclesiastical and political history.

St Mary Redcliffe, or The Church of St Mary the Virgin as it is known formally, is an outstanding example of English Gothic architecture and grade I listed building that is often confused by tourists for Bristol cathedral. It also comes pretty high on those fanciful lists you sometimes see of ‘Catholic churches we’d really like back’.

Along with the nearby Bristol Cathedral, both churches have spent the past two years dealing with demands to remove stained-glass panelling that was erected in tribute to local 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston (1613-1721). The wealthy Bristolian’s role in the notorious trade attracted global attention in 2020 when civil rights protestors hauled his statue from its plinth and dumped the bronze effigy into Bristol harbour.

Within days, the statue of another slave trader, Robert Milligan, who owned 526 slaves in Jamaica, was removed from outside the Museum of London Docklands and Liverpool University also agreed to rename a student hall of residence named after former prime minister William Gladstone, who opposed abolition in the 1830s (but later called slavery “the foulest crime”). Thousands of Black Lives Matter protesters, backed by Oxford city council, also called for the removal of a memorial in Oriel College to British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who supported apartheid-style measures in southern Africa.

Back at St Mary Redcliffe, it has been argued for some time that the stained-glass panels celebrating Colston were incongruous and might have to go, but the toppling of his statue and subsequent national protests made the task unavoidable.

Pic: Removal of the Colston panels in Bristol Cathedral (with permission of Bristol Cathedral)

History reminds us that Colston knew about yet disregarded the deaths of thousands of African slaves when he was an investor and, eventually, deputy governor of the Royal Africa Company. The company’s records show that during his 12 year involvement with the company it embarked 84,500 Africans to work the American and Caribbean estates. However, recent studies indicate that only 65,200 disembarked, with 19,300 deaths at sea, nearly a quarter of the human cargo. Meanwhile Colston’s personal fortune grew by the modern equivalent of £5 million-£50 million, depending on how comparison is made.

Understandably, the Colston window in St Mary’s – with its motto of Go, Thou, and do likewise (Luke 10.37), from the parable of the Good Samaritan, could hardly be justified adorning a house of God. As the Bristol Diocesan Chancellor, the Revd and Worshipful Justin Gau put it: “I am . . . satisfied that the work and mission of the church are being hindered by the presence of the window.”

St Mary’s removed the Colston panes and replaced them with temporary plain glass, whilst it launched a competition for the design of the replacements. Entries came in from across the UK and the winning design was submitted by Ealish Swift, a Bristol-based junior doctor. Of the four new panels now in place, the first depicts Jesus calming the raging seas of the Middle Passage on a Bristol ship during the transatlantic slave trade; another celebrates the Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963, with Jesus among the protesters; a third depicts a diverse group of “neighbours” with the Suspension Bridge in the background; and, in the fourth, Jesus is depicted as a child refugee fleeing to Egypt in an inflatable raft.

“My design draws from the deep and complex history of Bristol, from atrocities of the past to modern-day concerns, to remind us of the journeys of our neighbours and how we have come to be together at this moment, looking forwards towards a shared future,” said Ms Swift.

“Jesus is depicted as multiple ethnicities to counter the Anglo-centric narrative of ‘white Jesus’, and running water flows between the panels to centre the designs in the sea-port city of Bristol.”

At a very basic visitor level the new panels are highly engaging, thought-provoking and vividly colourful, a vast improvement on the desperately dull and uninspiring Colston panels. At a deeper level they will no doubt raise profound and far-reaching questions about both the annihilation of artefacts and the redrafting of historic narratives, and even the nature of Christian representations and presumptions in religious art.

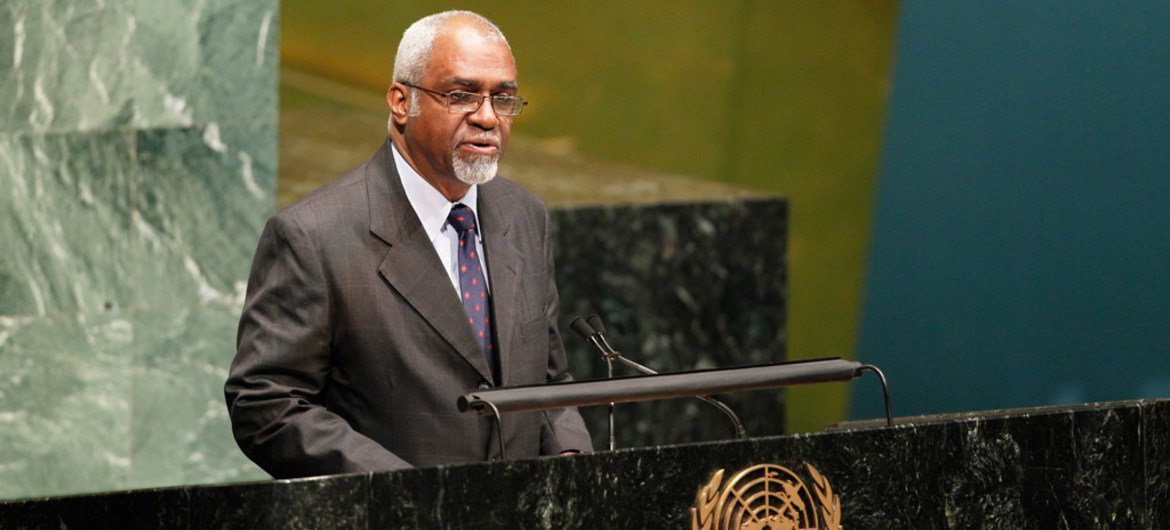

Whilst the replacement of the St Mary windows was completed this week with hardly a murmur of publicity, the broader debate about reparations for slavery is rapidly gathering pace. On Thursday a United Nations judge, Patrick Lipton Robinson, dropped a bombshell warning that the UK is likely to owe £18.8tn (yes,trillion) in reparations for its historic role in slavery.

Even that, said Robinson in a report he has co-authored, is an “underestimation” of the damage caused by the slave trade.

Pic: Judge Patrick Lipton Robinson (courtesy UN General Assembly)

“Once a state has committed a wrongful act, it’s obliged to pay reparations,” said Mr Robinson, who presided over the trial of Slobodan Milosevic, the former Yugoslav president. A member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2015, Mr Robinson was speaking ahead of his keynote speech at an event to mark Unesco’s Day for Remembering the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Abolition at London’s City Hall on Wednesday.

His Brattle Group Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery, which was released in June, calls for 31 former slaveholding states to pay reparations of some £87.1tn, but leaves it to the offending governments to work out how and when they are going to make the payments.

Needless to say the response has been less than enthusiastic, and reflects many decades of refusals and prevarications by complicit countries to engage with demands from Caribbean nations for compensation. Ealier this year, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak dismissed calls for the UK government to apologise and pay reparations for its role in slavery, the defence being that we should not become fixated with the past, rather we should move forward and devote our energies to learning from previous mistakes.

Although it has been ignored until recently, British authorities and the monarchy were very active participants in the trade, which saw millions of Africans enslaved and forced to work, especially on plantations in the Caribbean, between the 16th and 19th centuries. Whilst we had a pivotal role in ending the slave trade with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, the British government has never formally apologised for slavery or offered to pay reparations, and that doesn’t seem likely to change soon, as successive recent prime ministers have been overtly bullish about the subject.

Judge Robinson said this week that he hoped that Mr Sunak would change his opinion on reparations, and added: “For me, it goes beyond what the government and the political parties want. Of course they should set the tone. But I would like to see the people of the United Kingdom involved in this exercise as a whole.”

It’s a noble thought, but one that’s unlikely get a warm response, however preoccupied the British public might seem to be at the moment with social reform. Protest and fine words come easy, but putting one’s hand in one’s pocket to compensate for the wrongs of some forgotten, unrelated ancestor in the dim and distant is a very different matter.

Earlier this week, Charlie Gladstone, the great-great grandson of 19th-century Liberal prime minister William Ewart Gladstone, said that he and his family have begun reparations for their ancestors’ particular involvement in the slave trade. William Gladstone’s father John was an unrepentant slave owner who received one of the largest compensation payments (£10m in today’s money) from the British government when the 1833 abolition act forced him to relinquish the 2,508 slaves he owned and controlled in British Guyana and Jamaica.

Whilst John’s views were unambiguous, his son William had a complex and still hotly-debated relationship with slavery – as a politician he was closely involved with the claims of his father, and supported compensation for slave-owners, the system of apprenticeship, and the defence of the West India interest over such matters as sugar duties. Later in life he changed his views and in 1850 declared in parliament that slavery was “by far the foulest crime that taints the history of mankind in any Christian or pagan country.”

Pic: William Ewart Gladstone

In a candid interview with the Guardian few weeks ago, Charlie said he was moved to tears when he learnt the true extent of John Gladstone’s involvement in slavery.

“I felt absolutely terrible. I really, really hated it. It was a shock and I felt absolutely sick,” said Charlie.“Slavery is a crime against humanity and to have someone in the family involved in that is horrendous.”

So far the Gladstones have donated about £60,000 to fund a research post at UCL, the university that revealed the true extent of Britain’s slave-owning past and the £20m paid to 46,000 British slave owners in compensation. A further £100,000 will help set up a research department at the University of Guyana, with each family member making a contribution.

Eton-educated Charlie, who is the current owner of the rambling Gladstone estate in Hawarden, north Wales, has undoubtedly benefitted from the wealth of his more dubious ancestors, and acknowledging those wrongs and making reparations is certainly a moral and decent act. But what happens when calls for reparations extend to those who feel they have no direct connection nor have received any benefit from the racial crimes of the past? In blunt terms, should the British taxpayer of today have to pay compensation for the acts of unrelated citizens in the past when there is no obvious benefit the contemporary citizen enjoys as a consequence of those historic actions? That’s the dilemma confronting legislators, and one that’s only going to get sharper.

For those championing the case for reparations, who understandably see the world through a very different glass, the benefits of past oppression are obvious to see – the exploiting nations and their citizens are still benefitting from economic and societal advantages that were carved out directly from the slave trade, and an attitude that one group of citizens of the world could have a predestined superiority over another.

Furthermore, the reticence of exploiting nations and their citizens to recognise such historic wrongdoings, and to demonstrate any willingness to make amends, is a denial of repentance. Or to put it another way, the failure to recognise and make reparations for slavery is to perpetuate the wrongdoing. It could even be argued that to draw a blindfold over our eyes when we ourselves have legislated and acknowledged that these acts were the wrongdoings is to double the insult, and constitutes an ongoing form of slavery.

The moral argument that, ‘because Person A carries out an immoral act, Person B should be exculpated from blame for carrying out the same immoral act,’ is both illogical and incorrect. That is why we might see no offence in leaving old statues to despots lying around our cities, having buildings that are named after them or passing by dull Victorian glass panels in churches, but others see it differently.

Even before Colston or Gladstone’s time there was more than enough public condemnation for such powerful men to know the moral value of their involvement in the transatlantic trade in slaves. They knew very well what their actions were; they simply didn’t care and – in the interests of increasing their own person wealth – they turned a blind eye to the atrocities they knew they were committing. Two centuries later of relentless efforts to get the horrors of slavery recognised, there’s really no justification for consigning such events to history and washing our hands of any culpability.

Ignorantia juris non excusat, as the Bible says (Leviticus 5:17).

From prehistory, through Plato, Socrates, Our Blessed Lord and down through all the ages, it’s hard to know how humankind ever came to develop the opinion that one person is superior to another in the eyes of God, but the least we can do is not to perpetuate the myth.

Joseph Kelly is a Catholic publisher and theologian

________________________

• What do you think about reparations for the slave trade? Have your say on our discussion forum …