Urgent action is needed to tackle the dark and disturbing world of child trafficking, says Joseph Kelly

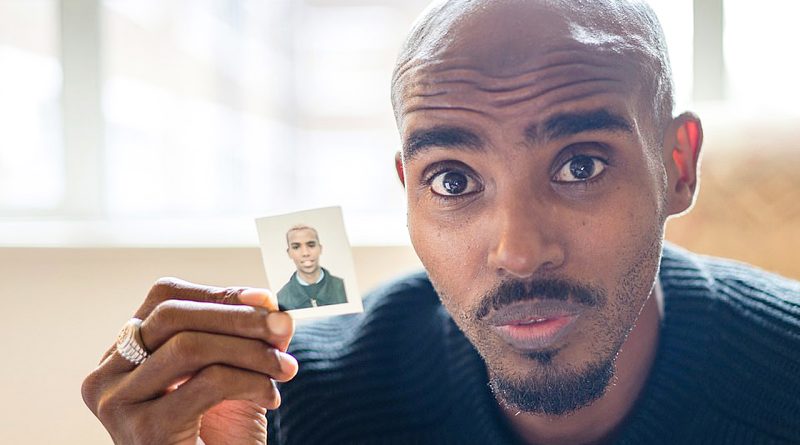

“Most people know me as Mo Farah, but it’s not my name or it’s not the reality. The real story is I was born in Somaliland, north of Somalia, as Hussein Abdi Kahin. Despite what I’ve said in the past, my parents never lived in the UK.”

With that simple admission, one of the most iconic figures in British sport led TV viewers through a bruising one hour journey into the dark and disturbing world of child trafficking.

“When I was four my dad was killed in the civil war. I was separated from my mother, and I was brought into the UK illegally under the name of another child called Mohamed Farah,” the athlete continued.

“To be able to face it and talk about the facts, how it happened, why it happened, it’s tough. The truth is I’m not who you think I am. And now whatever the cost, I need to tell my real story’.”

In a highly emotional documentary that has become the talk of thew nation, four time Olympic gold medal winner Sir Mo Farah unwrapped the truly harrowing story of how he had been trafficked to the UK from Somalia as a child.

Mo still carries some cherished memories of his early childhood growing up in a subsistence farming family in the impoverished Republic of Somaliland, a de facto state in the Horn of Africa. Somaliland has the fourth lowest GDP per capita in the western world and a youth unemployment rate in excess of 70%.

Livestock rearing is the backbone of the economy, but this fragile living is regularly shattered by the ongoing war in southern Somalia between Islamist insurgents on the one hand, and the Federal Government of Somalia and its African Union allies on the other.

In 1987 when he was just four years old, Mo’s family was torn apart when his father became a victim of the war.

“’My dad went to look after cattle and never came back,” said Mo.

“Due to the civil war happening between the North and the South, there were a lot of people fighting where he was. There was a massive bazooka shot. It hit the ground and flew into pieces and one piece hit him on the head and just straight off, off the head there. To me the hardest thing is, till this day, is like, I don’t even know what he looked like.”

Unable to guarantee a life for her children, his mother made the wrenching decision to send the young Hussein and his brother Hassan to live with relatives in Djibouti, and thus the remarkable story of Mo Farah began.

With all contact with his birth family severed, Hussein was smuggled into the UK illegally in 1993, aged just nine and using another child’s identity. For years the fate of that other child whose identity he was given haunted Mo Farah.

As an outsider in a strange family, Mo revealed that he had to cook, clean, change nappies and wash the unnamed mother’s children “if I wanted food in my mouth”.

He said the woman, who is still believed to living in Hounslow, told him: “If you ever want to see your family again, don’t say anything”.

The documentary caused an avalanche of emotion, with viewers left in astonished disbelief that such a vulnerable child could be torn from his family, trafficked so easily into the UK and entrapped into a life of slavery. The programme was all the more shocking for the fact that all of the parties – and especially the traffickers – are still around.

For Sir Mo Farah the programme has brought some considerable peace – he’s been reunited with his real family and the boy whose identity he was given, he’s been able to tell his harrowing story, and the years of deception, guilt and anguish have finally started to lift. He’s also been reassured that his British status is safe as he was too young at the time to be culpable, though the Metropolitan Police has launched an investigation into the traffickers.

For Mo, now aged 39, his resilience, his passion for running and the support of a sympathetic PE teacher, helped to free him from a life of servitude. He also received a lot of help and support from St Mary’s Catholic University, Twickenham, where he trained from 20012 until 2011, when he moved to the USA. In December 2012 he was inducted into the St Mary’s University Hall of Fame for Sport and he continues to keep in regular contact as one of the university’s leading alumni.

Sadly there are countless other trafficked children who do not get such breaks, and Mo’s decision to tell his dark and complex back story will undoubtedly shine a light on the many nameless victims of modern slavery who are all too often dismissed incorrectly as ‘illegal’ immigrants.

His story comes a very apposite moment – a Tory party that very recently committed itself to a highly questionable scheme to ship immigrants out to Rwanda and has been dragging its heels on Ukrainian refugees is looking for a new leader, and one that can draw a line under the chaotic Johnson years. Bashing benefits, creating wealth opportunities and de-taxing the rich have been mentioned already, but the slick campaign videos and rousing speeches are largely devoid of social concerns, and there’s been a conspicuous silence from all but one of the candidates (the ultra-right Suella Braverman) on the immigration debate. Understandably most legislators consider this subject far too toxic to tackle.

However, global conflicts, economic turmoil and climate change are creating unique mass migrations of people, and the wise know that a looming global food crisis caused by lack of grain and fertiliser will soon see whole desperate populations on the move, with many vulnerable and isolated individuals among them.

According to the Home Office, more than 10,000 people were referred to the UK authorities in 2020 as possible victims of slavery, many of them flling into the hands of criminal gangs who force them into domestic servitude, sex work and drugs rings.

Whilst the Mo Farah story is unlikely to soften the hearts of the current Tory leadership contenders, it may just help to change a narrative that currently sees irregular migrants as a problem to be dealt with, rather than as individual human beings at extreme risk.

The Mo Farah story has deep echoes of the life of St Josephine Bakhita. Born in 1869 in Darfur, Western Sudan, she was abducted by Arab slave traders when just seven years old. Bakhita was not her birth name, it’s the Arabic word for ‘lucky’ and was given to her by her captors. Such was the trauma of her abduction and subsequent life of domestic slavery that she became unable to remember anything of her birth family.

Josephine eventually gained her freedom, became a Canossian Sister, and died in Veneto, Ital in 1947. She was canonised by St John Paul II on 1st October 2000, and is the patron saint of human trafficking survivors. She is also the patron saint of the Santa Marta Group – an alliance of international police chiefs and bishops from around the world working together with civil society in a process endorsed by Pope Francis, to eradicate human trafficking and modern day slavery.

Speaking last year in Westminster Cathedral on the feast day of St Josephine, HE Cardinal Vincent Nichols – who is President of the Santa Marta Group – described modern slavery and human trafficking as “pitiable: a terrible wound in the flesh of humanity, indeed the body of Christ.”

“The organised criminal networks, which profit ruthlessly through the sale of our brothers and sisters as slaves and no more than commodities to be exploited, are taking full advantage of this chaos: over 40 million trapped today in modern slavery,” said the Cardinal.

In May 2021 another member of the Group, Bishop William Kenny CP, called on Home Secretary Priti Patel to modify its approach to immigration and modern slavery issues. In a strongly worded letter Bishop Kenny warned that government policy is overlooking genuine failings in the UK’s response to trafficking and modern slavery.

“The reality is that a significant proportion of victims are never identified, most of those who are do not receive adequate support, and prosecutions of criminals responsible for exploitation are extremely rare.

“Furthermore, the introduction of new barriers to entering and seeking asylum in the UK risks pushing more people into the hands of traffickers. Across the world it has been consistently demonstrated that policies criminalising those seeking sanctuary and introducing new border security measures do not save lives but are simply a charter for trafficking.”

Priti Patel obviously wasn’t listening as, despite extreme misgivings even from her own parliamentarly colleagus, the Home Secretary blundered on this year with her disastrous Rwanda flights plan.

Whilst there may be some ideological distinction between an English Channel asylum-seeker and a trafficked innocent child, the language of government continues to blur these distinctions dangerously. The current administration has always leant towards criminalising the victims rather than targeting the perpetrators, simply because that’s easier, cheaper and plays to the lowest kind of public prejudices. The great sadness is that maintaining and funding a punitive fortress system of obstruction, incarceration and repatriation is far more burdensome than an open, welcoming and supportive strategy towards the stranger on our doorstep.

The irony is that, for all the blustering and rhetoric, the UK has a significant and growing trafficking problem, whether it’s the vulnerable coming into the country, or those already here – as the shocking Telford abuse and trafficking enquiry has revealed.

I’ve often argued that history isn’t changed by major things, but by small, random and often lateral events. The Mo Farah documentary lasted just an hour but has moved hearts and hopefully minds on the immigration issue.

After the programme was aired Cardinal Nichols praised Mo’s bravery in telling his story.

“I thank Sir Mo for his brave witness. This is a crime that permeates all countries and leaves a trail of misery as innocent victims are used as a disposable commodity by unscrupulous criminals. This is an evil crime and should not be acceptable.

“The UK has a Modern Slavery Act and the United Nations has prioritised ending human trafficking in its Sustainable Development Goals. Together, inspired by survivors of human trafficking including Sir Mo, we must collaboratively act in this struggle. I call on Government, as well as leaders across civil society, to re-double our efforts to abolish human trafficking and modern slavery.”

As well as raising urgent questions for government about how Mo and thousands like him come to be exploited, please God his brave witness will make us all far more alert to the fragile circumstances of the many strangers in our midst.

Joseph Kelly is a Catholic writer and publisher and founder of www.thecatholicnetwork.co.uk

_____________________

![]()

Pic: courtesy BBC

Thank you for the article on trafficking….I couldn’t agree more and it pains me that so little is done to unover the dreadful practice in this country. Before Covid I belonged to a small Anti Modern Slavery

group set up by the Anglican bishop Alistair Redfern who together with Cardinal Nichols put some good practices into operation (Safe Car Wash etc.) but interest in being actively involved is scarce. I just wish we could do more…..thank you again and perhaps if we keep highlighting the situation we will eventually lessen the activity.