27 Years on, Anscombe Centre raises worrying trends in Oregon’s assisted suicide system

Today marks 27 years since the implementation of Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act in 1998. In that time, as a recent piece in the Journal of Medical Ethics Forum and an article in BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care have both highlighted, concerning trends have become apparent, says the Anscombe Bioethics Centre.

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre is an Oxford-based research institute serving the Catholic Church in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Established in 1977, the Centre promotes the study of Catholic bioethics in service of the common good. According to Anscombe, the latest reports reveal that:

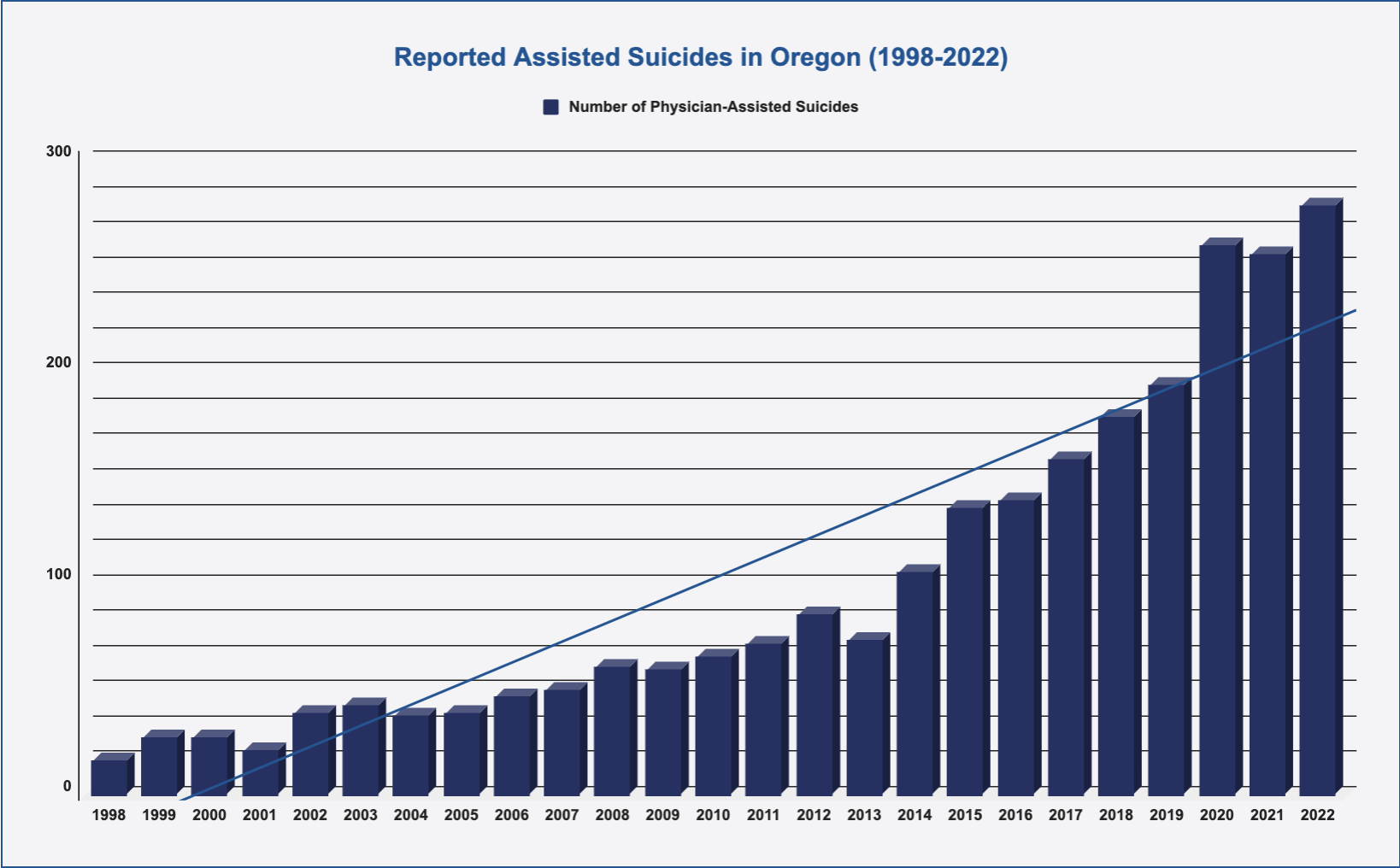

- The numbers of people committing assisted suicide has risen by 1,637% from 1998 to 2022 (the last year for which records exist).

- The proportion of patients reporting that they opted for assisted suicide because they feel a burden on family, friends, and other caregivers has risen from 13% in 1998 to 46.4% in 2022, indicating a dark turn in social attitudes brought about by assisted suicide in that State.

- At the same time, the proportion of those presenting for assisted suicide who were referred for psychiatric evaluation prior to assisted suicide has dropped from 31.3% in 1998 to 1.1% in 2022.

There has been a reduction in the length of the physician–patient relationship from a highpoint of 22 weeks in 1999 to the low-point of 5 weeks in 2022, Says the Insitute.

In a press release issued this afternoon (Friday 27th October), the Insitute says that these are just some of the concerns which have been raised in Oregon, and even these are based “on the little we are allowed to know”.

“The Death With Dignity Act Report admitted in its first year that ‘[W]e cannot detect or collect data on issues of non-compliance with any accuracy’, with other reports admitting that ‘[O]ur numbers are based on a reporting system for terminally-ill patients who legally receive prescriptions for lethal medications, and do not include patients and physicians who may act outside the law’. Oregon’s law requires doctors to report any prescription they make of lethal drugs, but there are no penalties for those who fail to report, and so no enforcement of this requirement. Reporting violations, such as non-compliance or under-reporting, are not monitored by the Oregon State Public Health Division,” Anscombe reports.

“Not only is data only voluntarily reported by doctors, but no information is collected from patients, or their relatives, and there is no official means by which the public can complain about assisted suicide abuses. it is little wonder that an editorial in The Oregonian in 2005 pointed out after almost a decade of the law’s operation that it established “a system that seems rigged to avoid finding” abuses or problems.

“This leaves large gaps where serious issues could remain hidden, and what we do know remains concerning. In 2022, there was no data on complications from the ingestion of drugs (such as vomiting or seizures) for 74% of cases. What data there was showed that 6% (just over 1 in 20) cases reported complications, and between 2010 and 2022 complications were reported on average in 11% (just over 1 in 10) cases.

Furthermore, Oregon and the other U.S. States that have adopted the Oregonian system have seen the weakening of safeguard restrictions over the last four years: the waiving of waiting periods, the allowing of nurses to prescribe the lethal medication, and the dropping of State residency requirements. Until 2019, it had been possible to argue that there was ‘no evidence of a “slippery slope”’ because ‘The Oregon law has remained unchanged since 1997’. This is no longer true. In recent years there has been a wave of expansion of such laws and further expansion is surely to be expected.”

Despite the lack of transparency within it, a quarter century of what data we have from Oregon and other States with similar laws show us that the more we know, the less reassuring the ‘Oregon model’ of assisted suicide seems to be,” the Institute concludes.

“After 25 years of evidence we see no slowing down in the expansion of physician-assisted suicide in Oregon,” said Professor David Albert Jones, Director of the Anscombe Bioethics Centre.

“The numbers of people opting to end their own lives keep going up, and at the same time we have seen an increase in people saying that they are seeking death because they feel a burden or because of financial concerns. At the same time, the law has been extended to include non-residents, and failures to report complications have increased. Across America as a whole, States that have adopted a similar law to Oregon have seen, on average, higher rates of ‘un-assisted’ suicide. The more we know, the more reasons there are to be concerned about what is happening in Oregon.”

- For more information on the Anscombe Bioethics Centre, see their website: www.bioethics.org.uk